MARIA MOLTENI

My work is conceptual, formal, socially engaged, deeply researched, collaborative, contemplative and mystical.

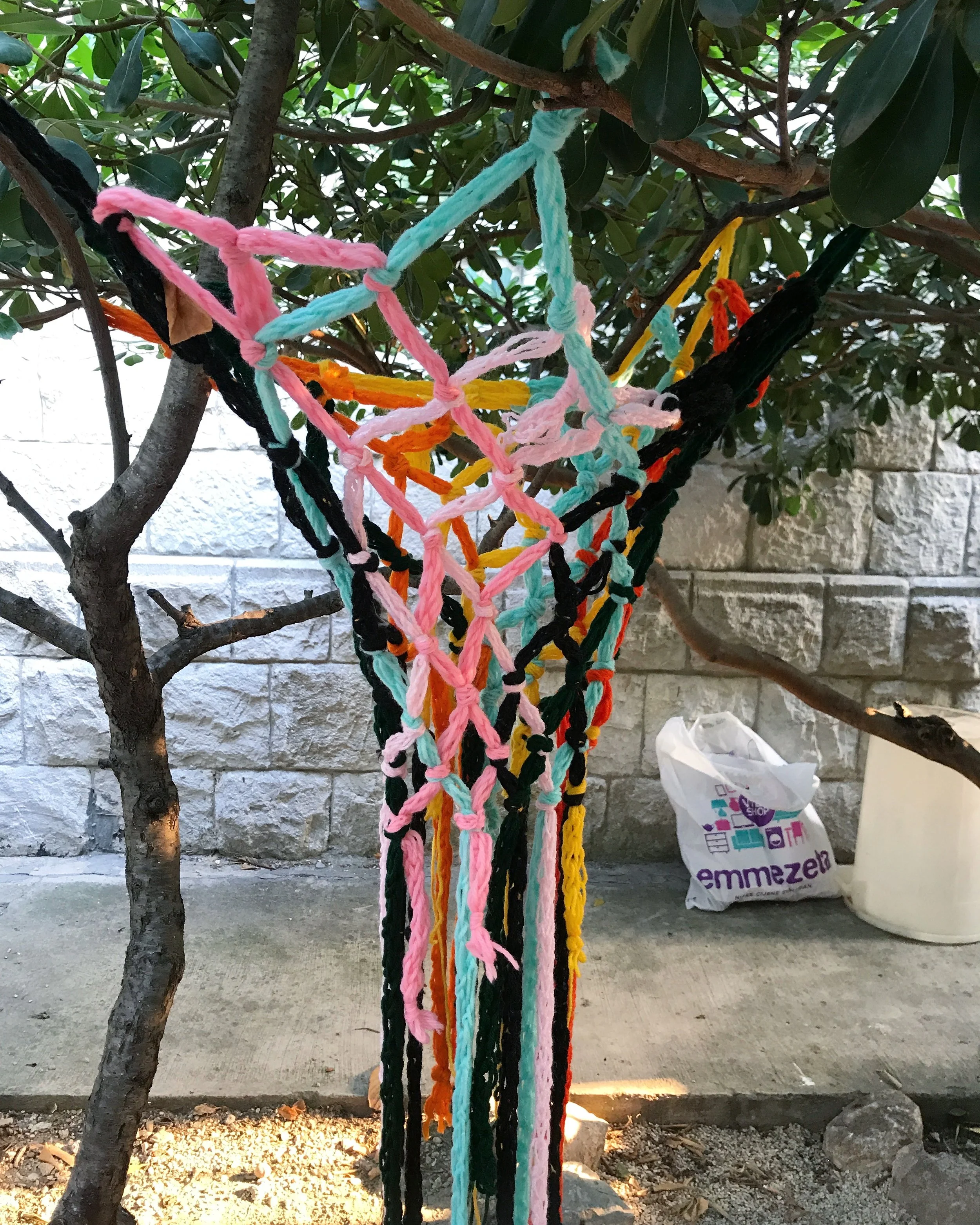

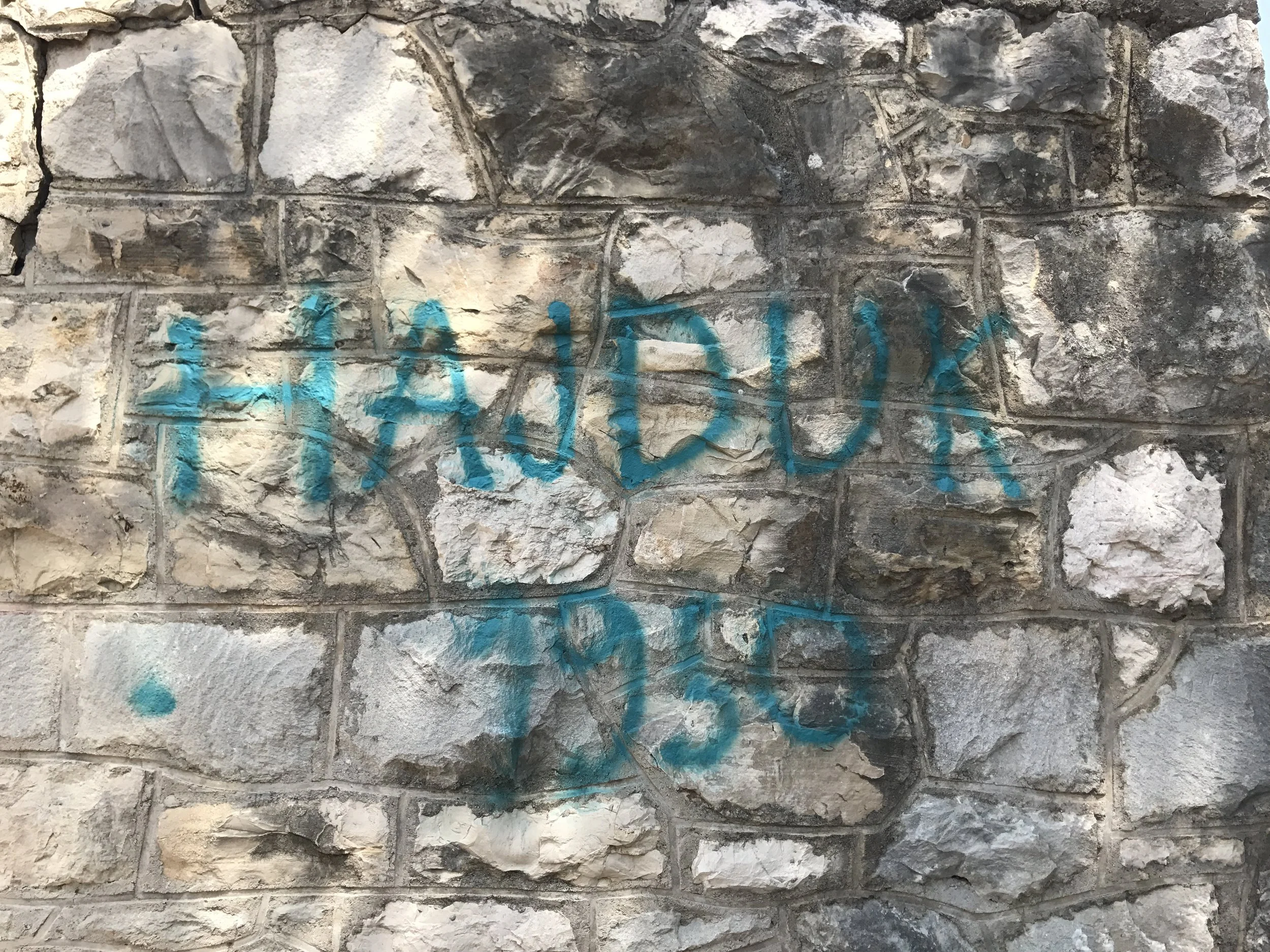

SOFT HAJDUK / SPLIT CROATIA

/

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·